#central-bank-independence

#central-bank-independence

[ follow ]

US politics

fromwww.mediaite.com

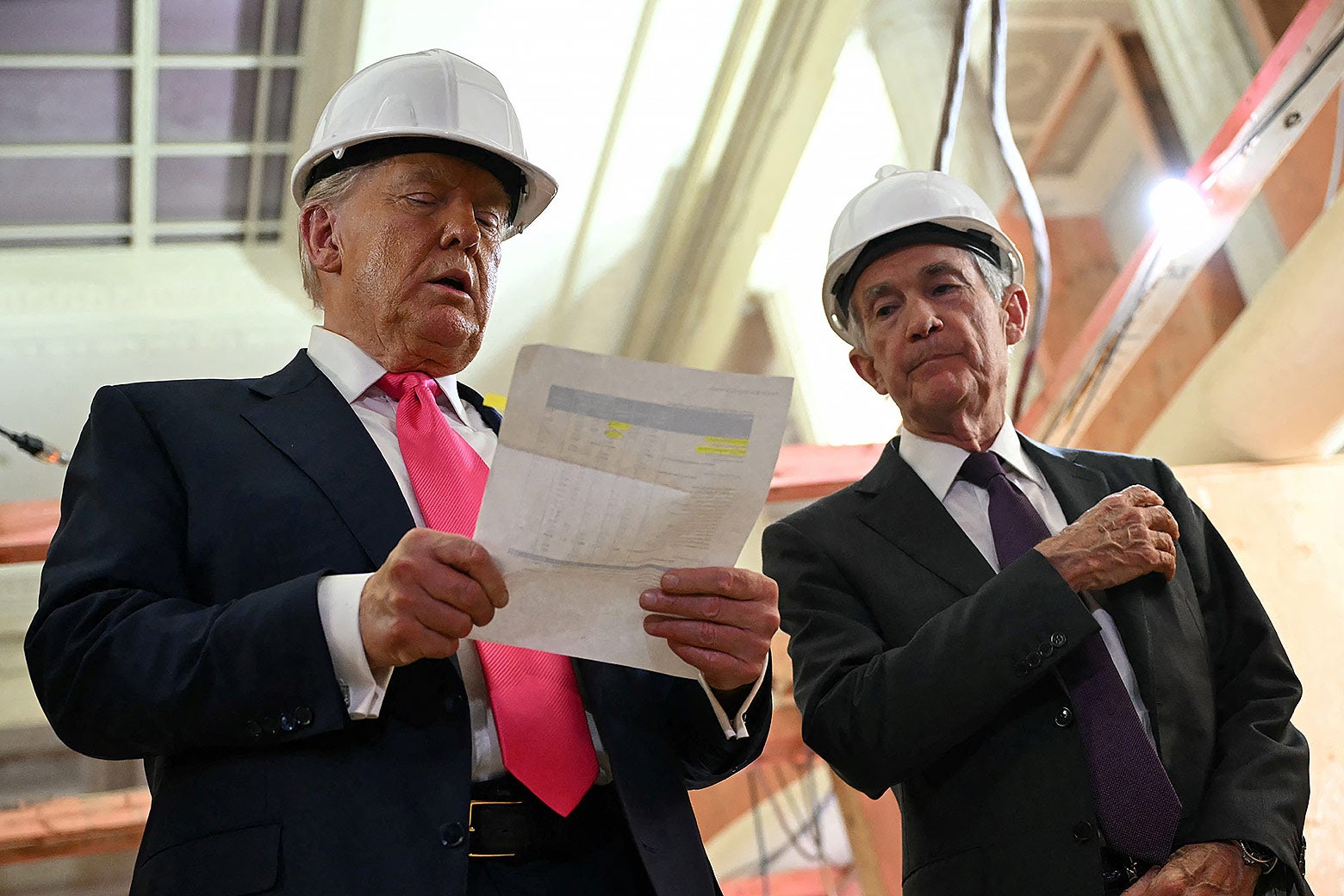

2 weeks agoCentral Bankers Across the World Unite in Full Solidarity' Behind Fed Chair Powell

Major central bank leaders jointly affirmed Fed independence and expressed full support for Chair Jay Powell amid a DOJ criminal investigation into Fed headquarters renovations.

fromBusiness Matters

4 months ago'Leap before you look': Baroness Morrissey on markets, leadership and free speech

I worry about complacency. Fiscal room for manoeuvre is thin across the developed world, and the toolkit that helped during the financial crisis-large‑scale QE, in particular-can't be mobilised in the same way again. Yields have risen sharply but mostly in an orderly fashion; we've not had many "cliff‑edge" moments outside Japan. That doesn't mean we're safe. If market participants decide they will only finance governments at much higher rates, the spiral can be vicious. We're vulnerable to that kind of shift in sentiment.

Business

fromwww.theguardian.com

5 months agoThe Guardian view on Trump and the Fed: independence is no substitute for accountability | Editorial

Donald Trump's attempt to sack the Federal Reserve governor, Lisa Cook, is the familiar authoritarian trick of bending institutions to serve the leader's immediate ends. The widespread condemnation is deserved. This is not some daring experiment in popular control of monetary policy. Yet what should follow censure is reflection. For the furore over Ms Cook has revealed a peculiar reflex: to defend the Fed's independence as though it were synonymous with democracy itself. But is independence of the Fed, or central banks generally, really that?

US politics

fromwww.theguardian.com

5 months agoLiz Truss backs Trump attacks on Fed and says reckoning' on way for central banks

I think there is a reckoning coming for the central banks, not just in Britain but also in the United States, also the ECB [European Central Bank], she told Bloomberg's Odd Lots podcast. Truss, who repeatedly criticised economic orthodoxy during her brief spell in Downing Street, argued that unelected central banks were able to undermine elected politicians. It's also very difficult, as I found as prime minister, to combine fiscal and monetary policy if you don't hold one of the levers. So I think it's got to change, she said.

US politics

US politics

fromFortune

5 months agoThe markets' reaction to Trump hides a darker truth that puts the American economy at risk, Piper Sandler warns

President Trump's efforts to control the Federal Reserve threaten American exceptionalism, free markets, limited government, and central bank independence.

fromLondon Business News | Londonlovesbusiness.com

6 months agoTrade and Fed concerns weigh on the greenback

Recent reports suggested that Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent attempted to dissuade President Trump from firing Chair Jerome Powell. Concerns around central bank independence could continue to weigh on the currency, while the current political pressure could undermine the institution's credibility.

US politics

[ Load more ]