#labor-market

#labor-market

[ follow ]

#federal-reserve #inflation #interest-rates #unemployment #layoffs #monetary-policy #artificial-intelligence

fromFuturism

1 day agoIf You're a Real Person Looking for a Job, the Flood of Fake AI Job Applications Will Make Your Blood Boil

And beneath the official jobs data is a growing accessibility crisis. More and more job seekers are finding themselves shut out of the labor market - not because there are no jobs to be had, but because torrents of AI slop are crowding them out of consideration. Case in point: a few months back, tech publication The Markup posted an opening for an engineer role.

Careers

fromFortune

2 days ago'I just don't have a good feeling about this': Top economist Claudia Sahm says the economy quietly shifted while policymakers wait for the wrong alarm | Fortune

Economist Claudia Sahm is an expert (if not the expert) on the conditions that presage a recession and how policymakers should react as a result. She is the creator of "the Sahm Rule," an employment indicator monitored by everyone from central banks to the global financial giants. The Sahm Rule says that a recession is likely when the three-month moving average of the national unemployment rate rises by 0.5 percentage points or more, relative to the minimum of the three-month averages from the previous year.

US politics

Artificial intelligence

fromFortune

3 days agoStruggling to remain relevant during the AI water-cooler chat? Talk about your latest "new collar" hire | Fortune

Agentic AI is creating many new 'new-collar' jobs, prompting businesses to hire diverse technical and human-skill roles to implement AI transformations.

fromEngadget

1 week agoUS Congress members call for 'thorough review' of EA's $55 billion sale

Democratic members of the US Congress, as part of the Congressional Labor Caucus, penned a letter asking the Federal Trade Commission to "thoroughly review" the $55 billion acquisition of EA. EA confirmed the sale to the Public Investment Fund, or the sovereign wealth fund of Saudi Arabia, Silver Lake and Affinity Partners in September, but the deal is expected to close in the first quarter of 2027. Before the official change of ownership, the 46 House Democrats who signed the letter to the FTC are calling for more scrutiny into the impacts of the deal.

Video games

World news

fromFortune

1 week agoAI productivity gains are making the rich richer, and they'll wipe out jobs-but the IMF chief sees a silver lining for low-wage workers | Fortune

AI-driven productivity increases top wages, and higher-earner spending can boost demand for low-wage services, potentially raising employment for low-wage workers.

Careers

fromFortune

1 week agoWelcome to the 'skills mismatch economy': the shift from roles to skills is making your resume-and your job title-worthless | Fortune

Labor market faces a skills mismatch: workers signal generalist abilities while employers increasingly demand specialized, execution-oriented skills that remain scarce.

fromFortune

1 week agoThe rise of on-demand leadership in the AI economy | Fortune

A quiet but consequential shift is underway in the executive labor market. Companies are rethinking how they access senior judgment in the AI era. Rather than defaulting to full-time executive roles that command lofty salaries and long-term overhead, companies are increasingly turning to experienced consultants, strategists, and advisors to provide leadership on a limited and targeted basis. This is not a dilution of leadership, but a recalibration of where experience delivers the most value.

Artificial intelligence

Artificial intelligence

fromFortune

2 weeks agoThe shaky job market won't last: Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang is 'fairly confident' that AI will increase productivity and hiring-but there's a catch | Fortune

AI adoption will boost productivity and hiring long term, but will cause widespread job changes and require workers to learn new skills or be outcompeted.

Higher education

fromFortune

2 weeks agoWhy a college degree is still worthwhile-and the 3 things it can teach you that AI can't do | Fortune

College degrees remain worthwhile because they teach complex social interaction, creativity, and navigating complex environments where humans retain an edge over AI.

Business

fromFortune

2 weeks agoThe 4.9% mystery: U.S. economy sees productivity surge, but drivers remain an 'open question,' top economist says | Fortune

U.S. productivity surged to a 4.9% annualized rate in Q3, boosting output amid weak hiring and prompting debate over cyclical versus structural causes.

fromFortune

3 weeks agoA Supreme Court ruling that strikes down Trump's tariffs would be the fastest way to revive the stalling job market, top economist says | Fortune

"This reflects the direct effects of the tariffs on manufacturing, transportation and distribution, and ag-related businesses, which are steadily losing jobs, as well as the indirect uncertainty hit to hiring by most other businesses," he explained.

US politics

fromwww.housingwire.com

3 weeks agoDecember jobs data continues to support lower mortgage rates

Jobs Friday came and went without much reaction in bond yields because the labor market isn't breaking, nor is it getting stronger. Mortgage rates dropped into the 5s for a short time on Friday as a result of Trump's earlier announcement directing the GSEs to buy $200 billion in mortgage backed securities. The 10-year yield didn't move much after the report.

Real estate

Business

fromFortune

3 weeks agoTop economist says latest jobs data shows a 'gut-wrenching' labor market for the middle class | Fortune

The U.S. labor market shows slowing hiring and frozen worker mobility despite economic growth, creating a late-cycle equilibrium with stagnant quits and weak job creation.

Artificial intelligence

fromFortune

4 weeks agoBank of America CEO says he hired 2,000 recent Gen Z grads from 200,000 applications, and many are scared about the future | Fortune

Bank hires 2,000 top graduates from 200,000 applicants and plans to reinvest AI efficiencies into growth while acknowledging Gen Z's hiring fears.

fromwww.housingwire.com

1 month agoLogan Mohtashami's 2026 housing forecast

The reason mortgage rates are near yearly lows as we end the year is that the labor market has softened and mortgage spreads have returned to near-normal levels. Without these two variables, mortgage rates would have stayed higher for longer. My 2026 forecast is for the 10-year yield to range between 3.80% and 4.60%, and for mortgage rates to range from 5.75% to 6.75%.

Real estate

US news

fromLondon Business News | Londonlovesbusiness.com

1 month agoThe significant events in the global economy over the past week - London Business News | Londonlovesbusiness.com

U.S. stocks hit records as 4.3% Q3 GDP growth driven by consumer spending boosted markets, amid mixed economic signals and cautious European gains.

fromwww.mercurynews.com

1 month agoConsumer confidence slides in December to lowest level since US tariffs rolled out

Consumers confidence in the economy was shaken in December as Americans grow anxious about high prices and the impact of President Donald Trump's sweeping tariffs. The Conference Board said Tuesday that its consumer confidence index fell 3.8 points to 89.1 in December from November's upwardly revised reading of 92.9. In April, when Trump rolled out his import taxes on U.S. trading partners, the reading was 85.7.

US politics

fromwww.mediaite.com

1 month agoAdjust Your Meds': NewsNation Host Gets Endlessly Mocked Over Her One Word' to Describe Trump

She shared a segment from her show on social media and wrote, If I had to summarize the first year of President Trump's second term in one word, it would be: dignity. From his foreign policy to his domestic policy to his immigration policy, the goal has been restoring the dignity of the forgotten working-class men & women of this country.

US politics

Business

fromBusiness Insider

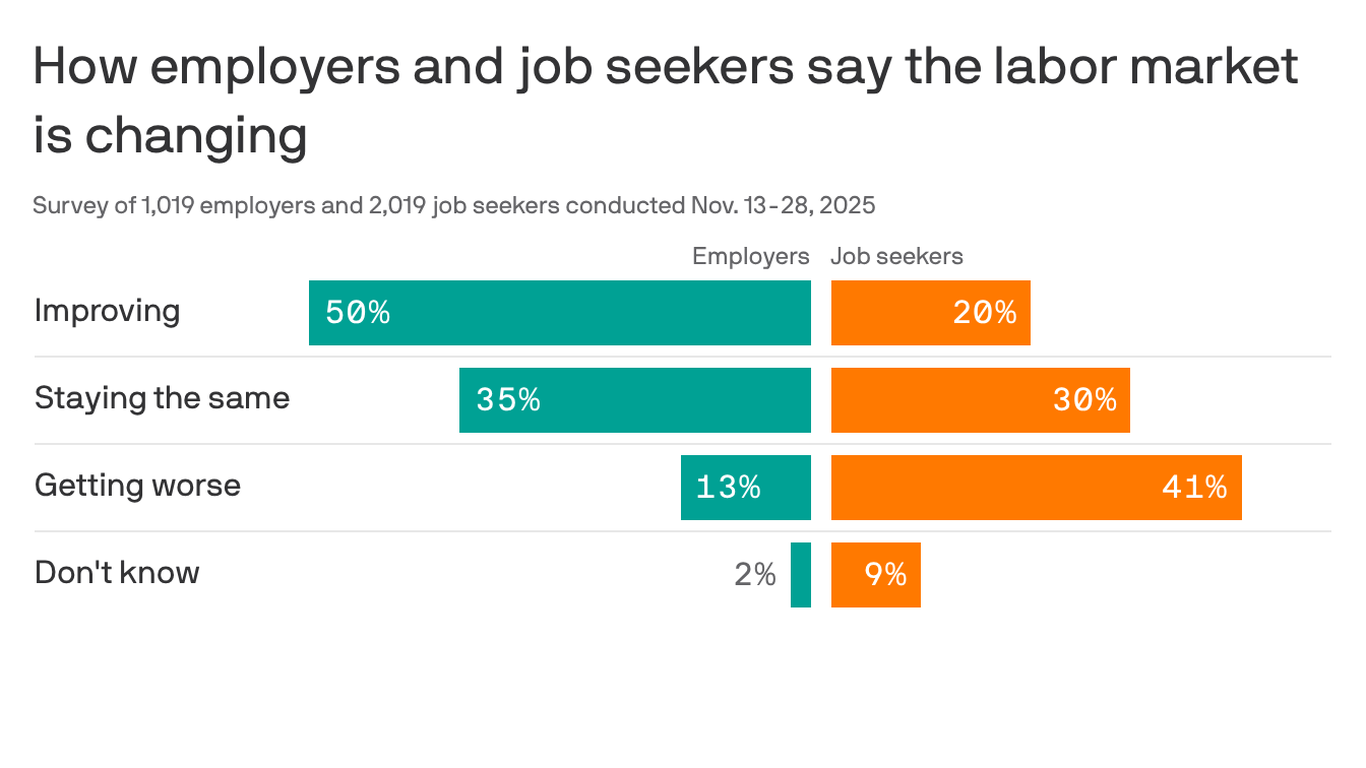

1 month agoUnemployment is low, but companies are slow to hire: How job seekers faced a Great Frustration in 2025

Job seekers in 2025 face stalled hiring, AI résumé filtering, ghost jobs, and fierce competition, producing prolonged unemployment and severe financial strain.

Artificial intelligence

fromwww.theguardian.com

1 month agoMost people aren't fretting about an AI bubble. What they fear is mass layoffs | Steven Greenhouse

AI-driven automation risks causing massive job losses, particularly among entry-level white-collar workers, potentially worsening unemployment and income inequality.

fromBusiness Insider

1 month agoRussia's wartime consumer boom is cracking as shoppers tighten their wallets

After years of wartime splurging, Russian shoppers are tightening their grip on their wallets - a shift that hints at growing stress in the country's economy. Growth in consumer spending has weakened across most regions, the Central Bank of Russia said in a report published Wednesday. In October and November, demand softened even as unemployment remained near historic lows and inflation expectations ticked higher.

Careers

fromwww.mercurynews.com

1 month agoOpinion: Bay Area needs to take bilingualism seriouslynow

In San Jose, Spanish isn't optional. It's essential. Hospitals, banksmost public-facing companiesaren't hiring Spanish-speaking workers for diversity's sake. They're hiring them because they need them. If a large share of your customers only speak Spanish, you need staff who can speak it, too. That's operational reality. But society still treats bilingualism like an add-on, a perk, a resume booster, and not what it really is: a critical part of our regional workforce infrastructure.

Education

[ Load more ]